Included below are several sections from my Thesis writing for my MFA at UT Austin:

Artist Inspiration

When I was little, my mother was an art conservator at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, TX, where her conservation lab worked on Frederic Church’s Icebergs in the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art. As a small child, I stared into the painting’s ice cave on the lower right, feeling swallowed by the submerged ice. Something deep resonated within as I was transported into the pictorial space in a way I’d never been before. This experience is a touchstone in my memory, and years later I am still driven to create portals to luminous, enclosed worlds.

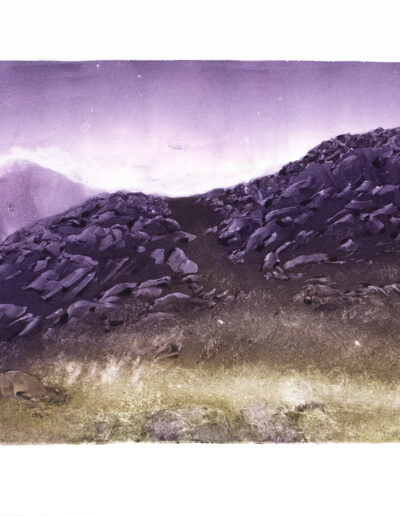

My interest in light and space in landscape continued as I was drawn to artists as diverse as John Constable, Edward Steichen, and James Turrell. For me, light is a symbol for energy and life within the picture plane. It creates both movement and atmosphere. With it I can create a narrative, and for inspiration I’ve looked to artists such as Albert Pinkham Ryder and Odilon Redon who capture drama in their nightscapes.

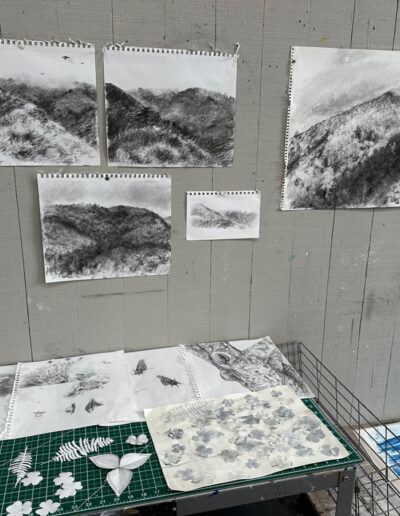

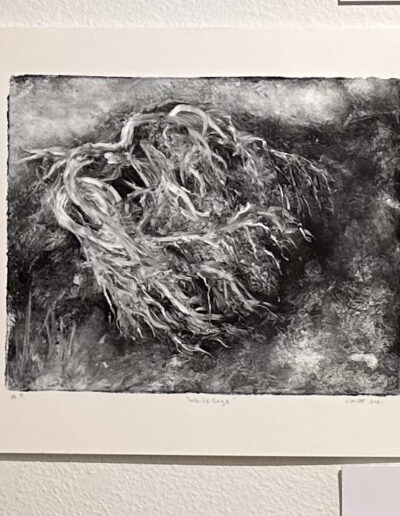

As I was drawing reeds blowing in 75 mph winds at PLAYA artist residency in eastern Oregon (Fig. 2.1), I looked to Charles Burchfield. How can you capture both sequence and sound in one still image? He captured movements of natural phenomena such as storms and wind and found ways to portray the sounds of insects and birds with repeated marks in painting. Burchfield also elevated the medium of watercolor by working large-scale, making it his primary medium rather than a sketch for oil paintings.

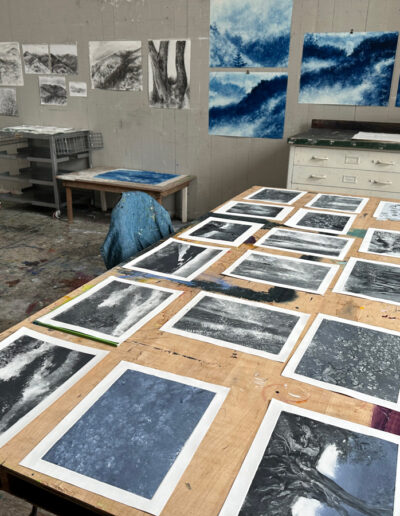

The work of Hercules Segers also caught my interest, a printmaker who created endlessly detailed etchings of dreamlike landscapes, invented sugar-lift, and inspired artists such as Rembrandt in his creative use of printmaking. He was highly experimental: hand-coloring plates, hand-cropping images, running coarse materials through the press to create texture, and adding watercolor layers with intaglio, breaking rules in printmaking as early as 1618 CE.

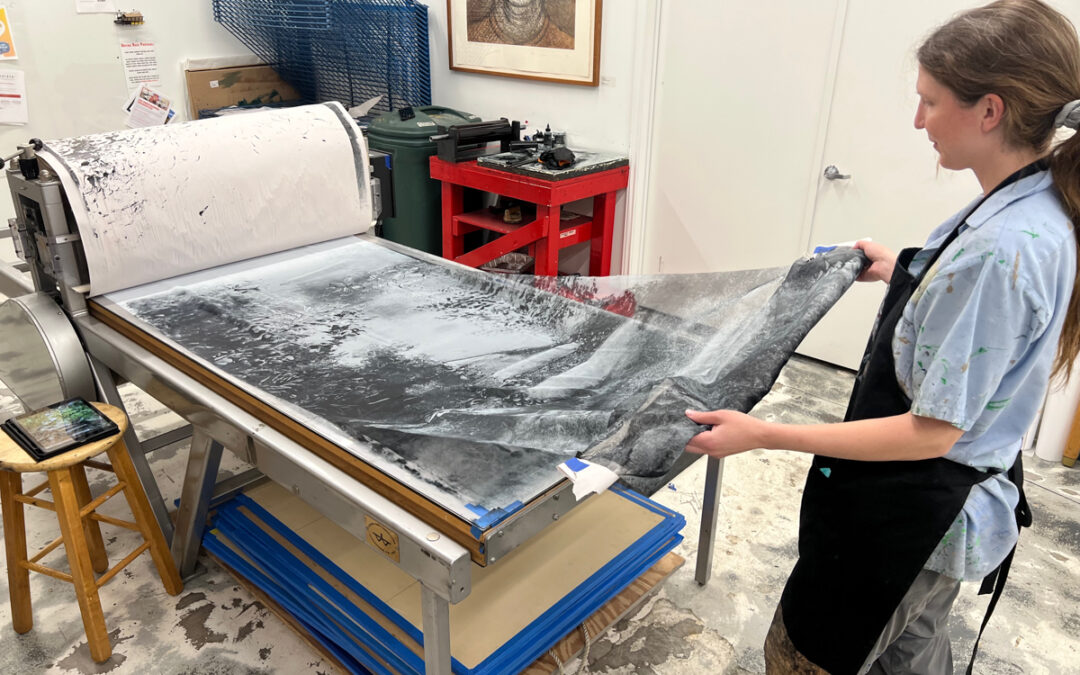

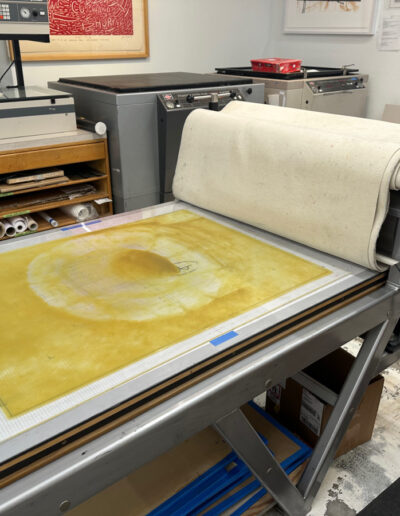

Emboldened by such artists, I use unconventional mark-making tools and methods in my work. I worked primarily in large-scale ballpoint, ink, and marker drawings for years, challenging conventional drawing sizes and creating light and shadow with masses of circular marks. Now as a printmaker, I’m finding ways to break away from the limitations of the plate, such as using the press bed as the plate and creating large-scale monotypes on fabric. I’m interested in how using different mediums in uncommon ways creates textures and effects that surprise me.

Another component I consider is the space the work inhabits. I am inspired by light and space artists, earthworks, and installation artists such as Turrell, Christo and Jean Claude, and Andy Goldsworthy. Experiencing their work has an immediate effect, where you respond to them even before you mentally process what you are seeing. I use both large and small-scale work intentionally to draw the viewer into the work in distinct ways. The small monotypes act as a portal to another space while the large works hold a three-dimensional presence you must walk around to experience. They cannot be replicated on a screen. This use of scale activates the presence of the space between the viewer and the work.

Ecological Inspiration

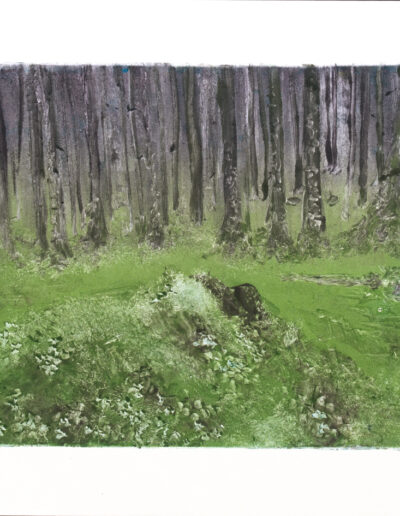

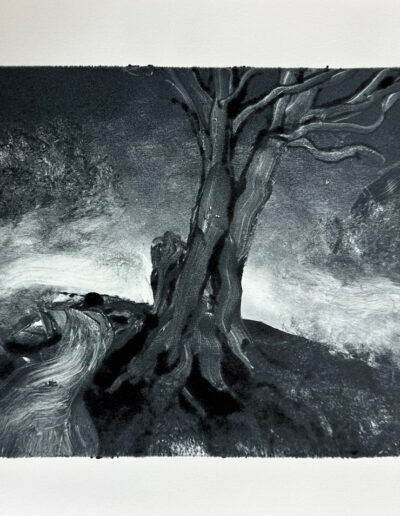

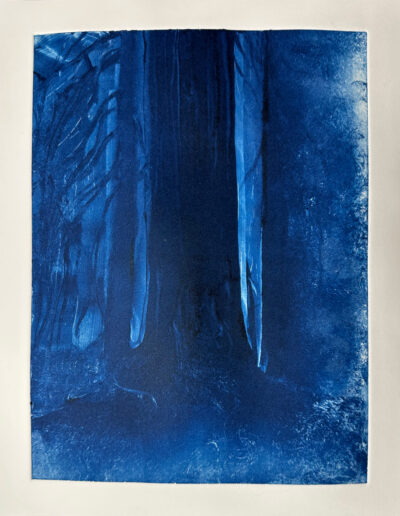

When I was an undergraduate class at Hampshire College, I took a class on writing about spirituality in a cabin in the woods of western Massachusetts. One day, a classmate made the observation, “When you’re in these woods, does it ever feel like the woods are looking back at you?” I’m from the plains of Texas, and this observation on the ever-present northeastern woods surrounding us struck a chord. It was the first time I’d been in such an absorbing black atmosphere. The woods receded into unknowable shadows, potent with hidden creatures as large as bears (Fig. 3.1).

In In Praise of Shadows, Junichiro Tanizaki argues that traditional Japanese architecture values the presence of shadows and the potent mystery they hold. Unlike a Western room in which light illuminates every corner, the eaves recede indistinguishably and silhouettes emerge from the darkness. This “magic of shadows”[1] allows for the unknown to emerge, as if from out of a void. He writes:

Have you never felt a sort of fear in the face of the ageless, a fear that in that room you might lose all consciousness of the passage of time, that untold years might pass and upon emerging you should find you had grown old and gray?[2]

Within the thick shadows of this New England forest, I felt similarly transported to a realm beyond the human timescale. Listening to the katydids at night, I was present to their shortened experience of time, linked to seasons and blooms, perched on pine trees that have a much longer life cycle. Where do humans stand in this, and how would I know if I were still in my familiar realm or transported elsewhere in this darkness?

It seemed as if the trees had agency and sentience. This idea has stayed with me and directed my focus to the experience of trees as active participants living in the landscape. Reading The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wollheben brought evidence to this belief, in which he describes the ability of acacia trees on the African Savannah to emit a warning scent to other trees when they are being eaten by giraffes and other creatures. Once aware of the threat, the trees can change their taste to bitter, discouraging animals from eating them.[3] That they can communicate with other trees via scent solidified my perception of trees as sentient beings. They can also choose whether to crowd out other trees or leave room for them to grow, and to save a neighboring stump from decaying. But what makes them choose which to aid or not?

Every tree is a member of this community, but there are different levels of membership. For example, most stumps rot away into humus and disappear within a couple of hundred years (which is not very long for a tree). Only a few individuals are kept alive over the centuries, like the mossy “stones” I’ve just described. What’s the difference? Do tree societies have second-class citizens just like human societies? It seems they do, though the idea of “class” doesn’t quite fit. It is rather the degree of connection—or maybe even affection—that decides how helpful a tree’s colleagues will be.[4]

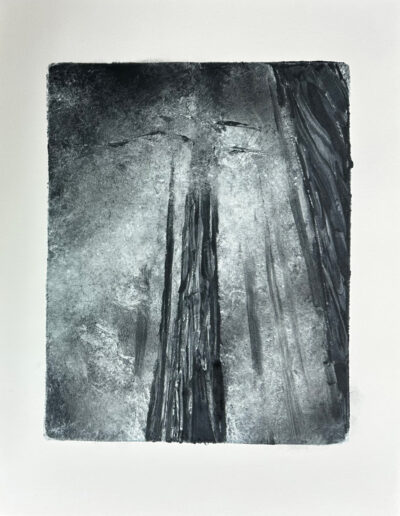

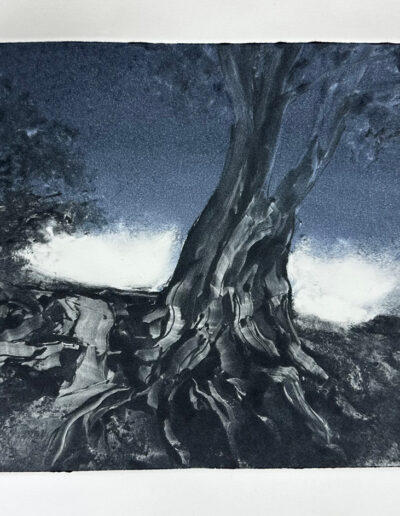

In focusing on the tree’s experience, the human-centric view of the world dissolves. On the scale of a tree’s life, would a day register as a moment? Would a human appear as a blur? And how does a tree experience sound—would it register a bird call? Imagining the tree’s perspective is a way for me to contemplate the will of the landscape. Through this inquiry, my installation work considers both human and flora sentience.

What is the landscape’s intention? What brings it joy? I want to make work for the landscape as the viewer (Fig. 3.2).

~~~

[1] Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, trans. Thomas J. Harper and Edward G. Seidensticker (Sedgwick: Leete’s Island Books, Inc, 1977), 20.

[2] Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 22.

[3]Peter Wollheben, The Hidden Life of Trees, trans. Jane Billinghurst (Munich: Ludwig Verlag, 2015), 7.

[4] Wollheben, The Hidden Life of Trees, 4-5.