Writings:

Nancy Elsamanoudi:

The Wonderful World of Vivacious Vixens and Dick Flowers

By Colleen Blackard

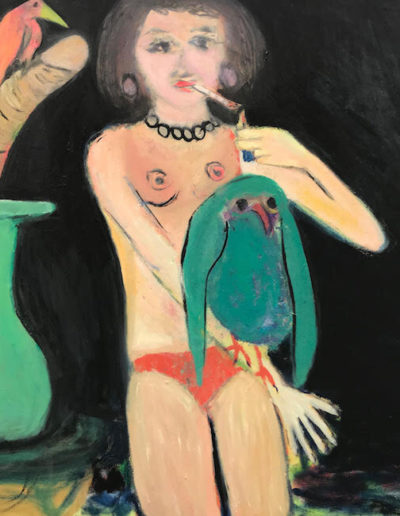

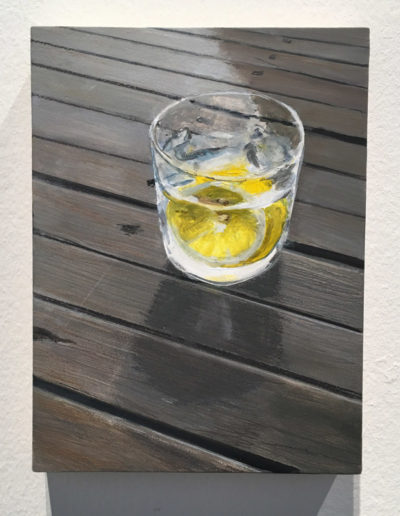

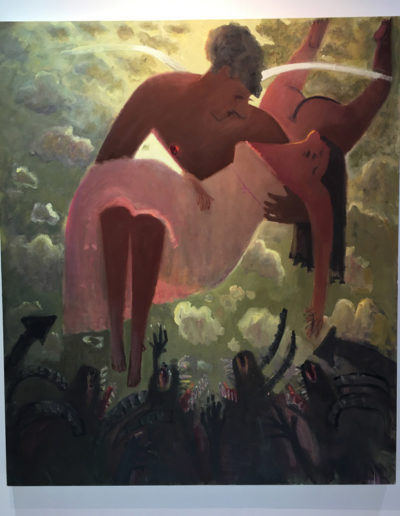

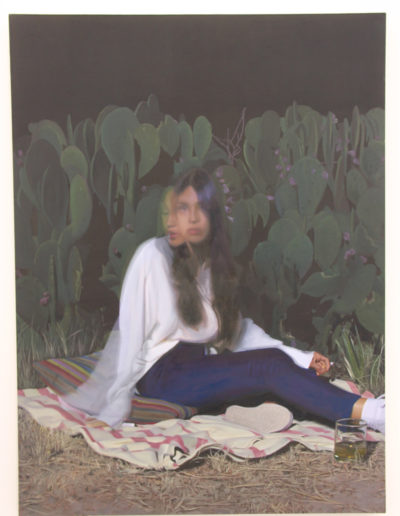

Happy Hour by Nancy Elsamanoudi

Nancy’s female subjects are anything but expected. Not the demure girls that were so idolized by male painters in Western art history, rather they are powerful heroines, at ease in their feminine form—a blend of softness and sexual prowess. They hold your gaze, needing to prove nothing. They own their space and are enjoying their liberation.

As I see these paintings, I compare them to Degas’ pastels of women in the bath—the male gaze through a keyhole. His women are undressed and vulnerable, going about their daily routines. While very human portraits, the view is coarse and unsympathetic. There’s no understanding of the intimacy he is seeing. In this way, Nancy’s naked figures are more like real women. They are even caught reading Baudelaire, Betty Friedan, and other social and philosophical texts. After all, why wouldn’t they? And while the viewer similarly has a window into their private life, it’s as if they are invited in. The figures are aware of the outside gaze, and welcome it. They are celebrating their humanity and carnal desires with no shame.

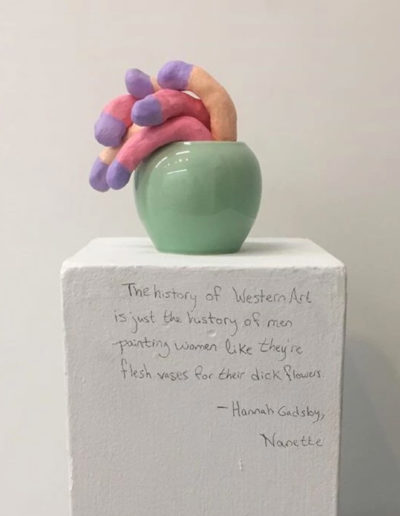

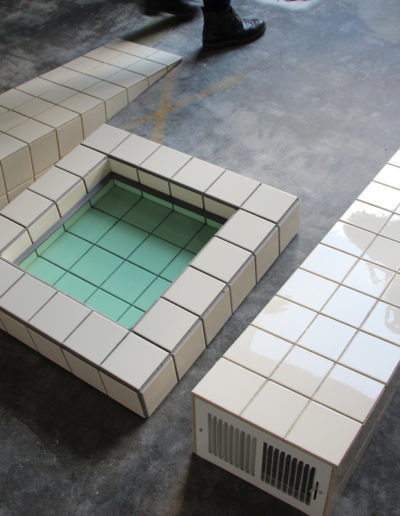

Many of Nancy’s paintings feature vases of flaccid “dick flowers.” Many of these fleshy objects droop pitifully, but make interesting decor. In “Perch,” a red bird even rests on one. These objects seem to help take back the stage for women by humorously reducing men into sexual objects. This symbolism becomes even clearer in a hand-written quote on the base of the sculpture, “Pink Flowers,” in which Hannah Gadsby describes the history of Western Art as “the history of men painting women like they’re flesh vases for their dick flowers.”

The bright palette and bold forms that make up Nancy’s paintings accentuate their playful and inviting nature. In “Tail,” one naked women with a unicorn horn and tail walks by while another lounges in red heels in a purple armchair next to a table with drinks, oranges, and a vase of dick flowers. The floor is vivid green against a pastel wall. The vibrant colors and outlined forms create an almost cartoon-like scene, keeping the focus on the figures the actions taking place. If these paintings had been rendered in more detail, they could become too intense for some viewers who might be embarrassed to see hand jobs and sex parties, like the group scene in “Two Fisted.” But in this symbolic form, the works can be easily accessed and the humor in these playful sexual acts comes through. This disarming aspect adds to the subtly subversive nature of the work.

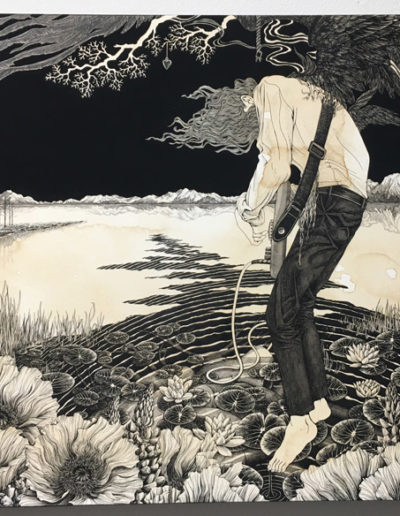

While visually communicating as strongly as cartoons, these bold colors and shapes also celebrate the language of paint. It’s amazing how the broad and active strokes that make up the flesh can have such softness and density. Even when simplified, they show knowledge of form, structure, and weight. In “Two Fisted,” one half of the painting is solely comprised of a ghostly white pair of legs receding into the black background. These legs have surprising depth. Their active energy brings to mind Susan Rothenberg’s painting, “Hands and Shadows.” They show a love of pure form and border on abstraction. In “Happy Hour,” the figure divides the painting into an abstract composition. The contortion of the woman as she crouches into a lunge while holding her drink forms a well-balanced configuration. The thin, downward point of the front neon red stiletto heel contrasts with the upward line of the straw in the drink behind it. Both shapes look ominous in front of the black background. I am enthralled by the color choice and structure of this painting, more so even than its subject-matter.

While at a first glance, these paintings may come across as whimsical scenes of erotic fantasy, they draw you in deeper to investigate inherent views on sexuality and the role of women in society. In this world where they are freely themselves, quite joyfully they look back out at you wondering, do you get it yet?

See more on her website: Nancy Elsamanoudi